New Year, Same Mission - Protecting Collections Part 1: Disaster Planning

As we enter into the New Year, it is common to see a lot of resolutions about what new and improved things the new year will hold. However, for many museums and historic institutions, the core tenets of historic preservation and protecting collections remain the same. The goal, no matter the year, is to preserve the unique history that each institution has.

One of the best ways to ensure that everyone at an organization is on the same page for this mission is to create and maintain a Disaster Preparedness Plan. This can be created comprehensively for the entire building, or it can be broken down to accommodate a private collection within an individual’s home. But the importance of a plan for disasters cannot be understated. When disaster strikes, do you have a plan in place to preserve the irreplaceable items in your care? There have been many, many times throughout history that disaster has struck and destroyed priceless legacies. (Personally, I am still heartbroken over the loss of the Library at Alexandria.) In 2018, a fire at the National Museum of Brazil destroyed approximately 90% of its collections. Just last month, a pipe burst at the Louvre in Paris and caused water damage to a substantial number of artifacts. Having a disaster plan can help reduce the risks of disaster and allow staff to know what to do if one should occur.

So what should a disaster preparedness plan include? There are a few key elements that should be included in a disaster plan to align with best practices and ensure that an organization or collection knows the proper steps to take in the event of an emergency. Preparedness should include plans for all relevant threats and emergencies, whether natural disasters, mechanical failures, or human problems. This means including information about preparedness measures in place. Where are the fire extinguishers? Have they been serviced within the last year? Are there up to date first aid kits? Have the smoke detector batteries been replaced? Where are the main power and water shut offs located? Risk prevention is a huge part of creating a disaster plan that will work.

But it should be relevant to the specific location. If the plan is written for a museum in coastal Florida, and it includes a blizzard plan but not a hurricane plan, it is not taking the location into enough account. It should address the needs of the staff, visitors, the building(s), and the archives and collections, with information on how best to protect and recover them. A disaster plan should include evacuation routes, floorplans, responsibilities, and safety areas. Another important inclusion in a disaster preparedness plan is the date of the last revision. In an emergency situation, it is important to know that the plan is relevant to the current conditions of a site. There should be a copy of this plan located somewhere both on and off site.

What makes a museum or historic site disaster plan different from many other institutions is the inclusion of collections specific information. This means that a solid emergency plan should include information on where artifacts are located in the building and the preventative measures in place around them, how to evacuate the collections in an emergency, and recovery information for post-disaster efforts. A list of prioritization can also be important; which items in the collection have the most value to an organization? Those items should be prioritized as the first items to be evacuated or recovered. Floor plans are relevant because not only do they highlight exit doors, but they also show where the collections are. These plans should also include the locations of the prioritized artifacts. The contact information for the individual in charge of the historic collections should be included in the plan, whether that is the curator, preservation manager, archivist, executive director, or board president. For organizations that have spent time on digitization or have digital collections, technological safeguards are another important consideration. Have backups of the files in multiple places and in multiple formats. Pest control as well as temp and humidity are also considerations to be made for collections preparedness. Having a plan in place is vital to the longevity of a collection.

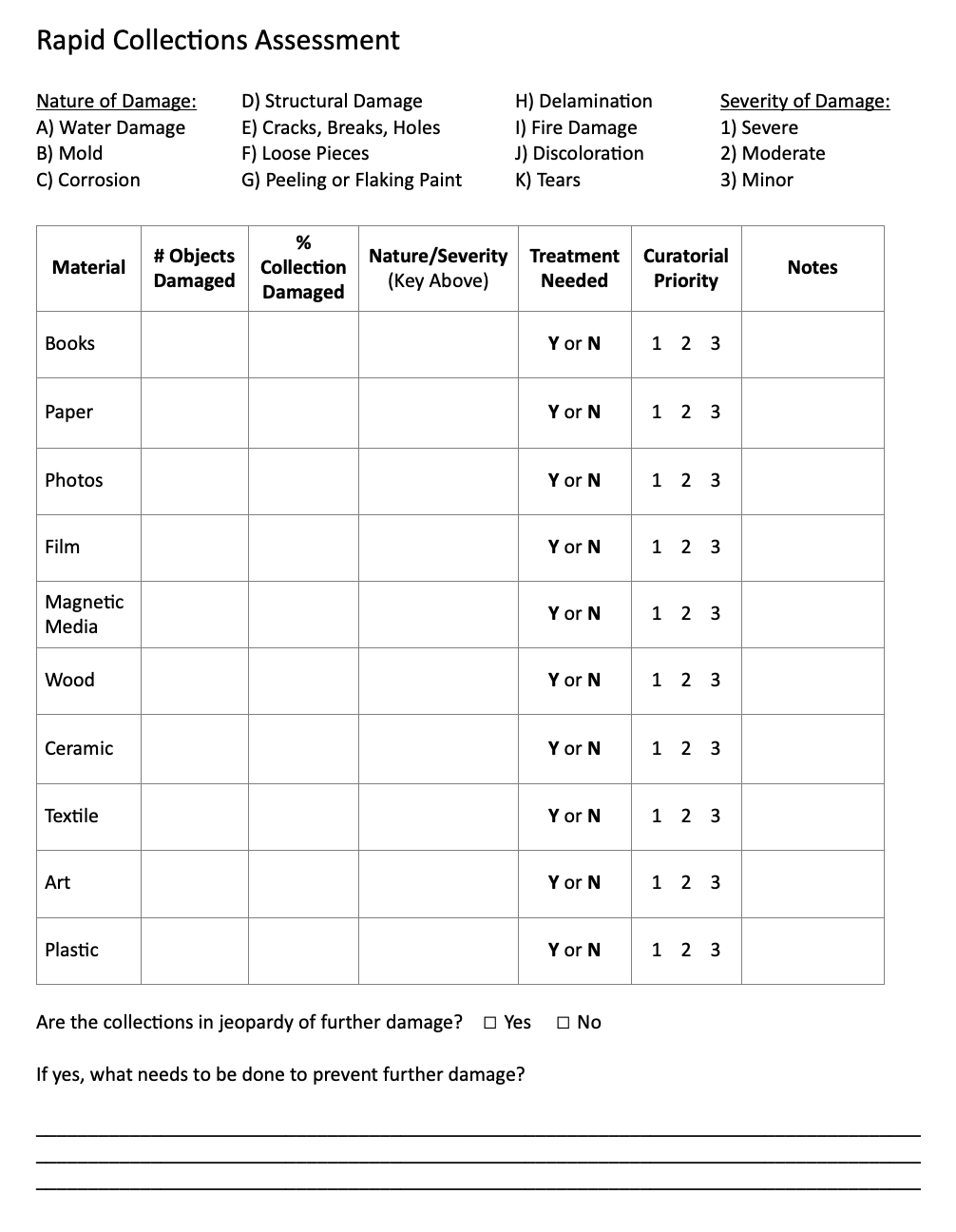

Salvage procedures are another important piece of a well-maintained disaster plan. In the event of a disaster that leaves a collection at risk, having a salvage plan for damaged materials is a way to take charge of a situation and encourage the best outcome from a terrible situation. A solid salvage procedure includes a collections removal plan and prioritization, handling instructions, and contact information for collections specific assistance organizations.

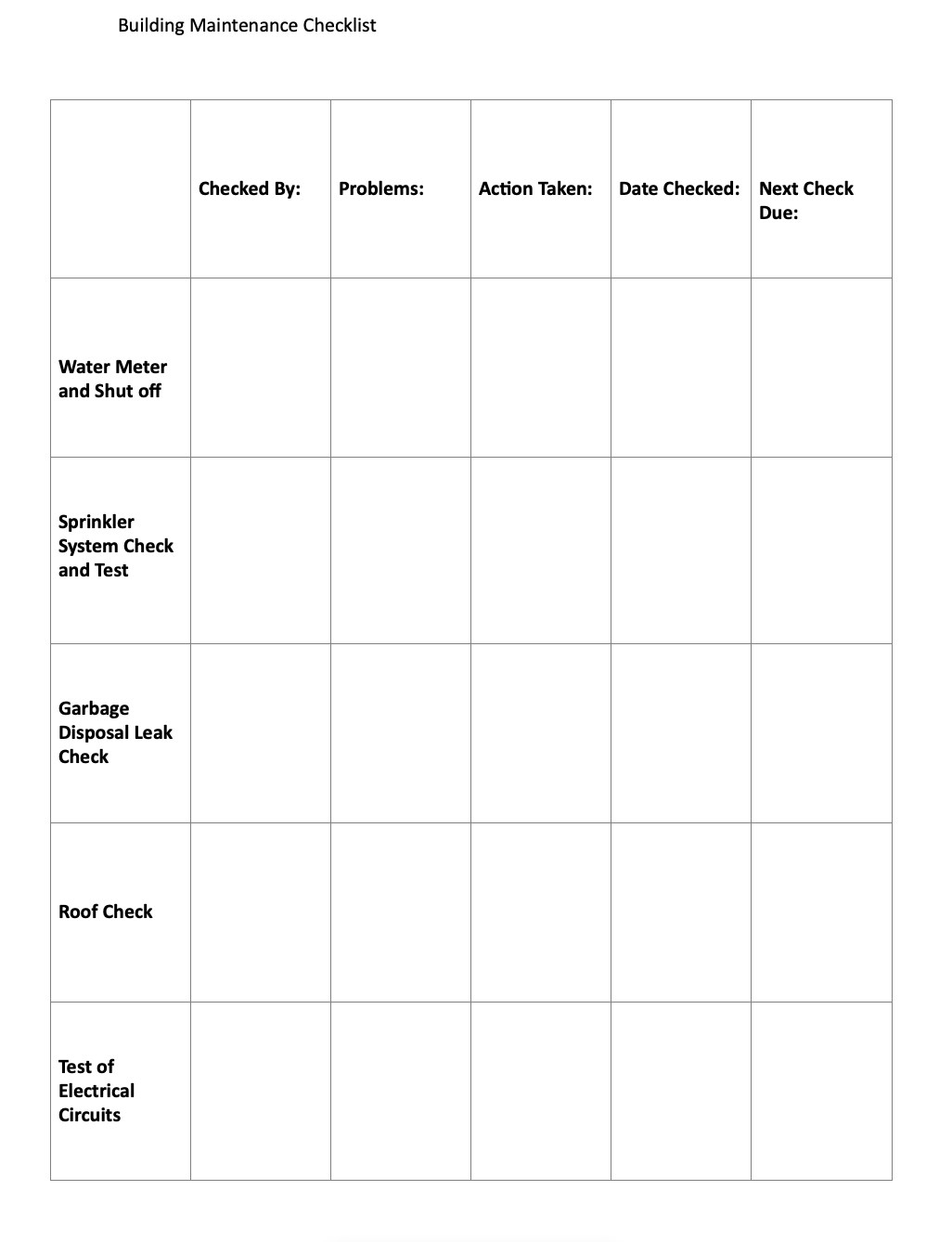

Forms and checklists are a vital part of any disaster plan. Below, I have included a few examples as they relate to prevention and collections salvage.

Thankfully, there are many resources for disaster planning in the museum and historic collections world. The American Alliance of Museums has many resources on disaster plan creation that can be found here. The Getty Conservation Institute published Building an Emergency Plan: A Guide for Museums and Other Cultural Institutions that contains a wealth of knowledge. Federal organizations such as OSHA and FEMA also have resources for general emergency planning.

If your organization needs help creating a disaster plan that is relevant to your historical collections, let’s schedule a consultation! I have worked with disaster and emergency preparedness plans, from tailoring a plan to be more collections focused to creating a plan from the ground up. I also have a certification in Emergency Planning through FEMA, and I would love to help your organization be better prepared for the worst case scenario. You can reach out to me through the Contact page or by sending me an email at crystal@curatingcollections.com.